Loyalty. Integrity. Honesty.

These were the character traits taught to the young cadets of the Oklahoma Military Academy in Claremore.

Although the academy and many of the cadets are long gone, its memory lives on in the OMA museum, and the lessons taught in those long-ago years were never forgotten by those who went through its hallowed halls.

On June 13, one of the OMA’s former cadets – Herman Mongrain Lookout – returned to the Hill to revisit and reflect on the lessons learned that shaped him into the man he became. Lookout was a cadet at OMA from 1959 to 1961.

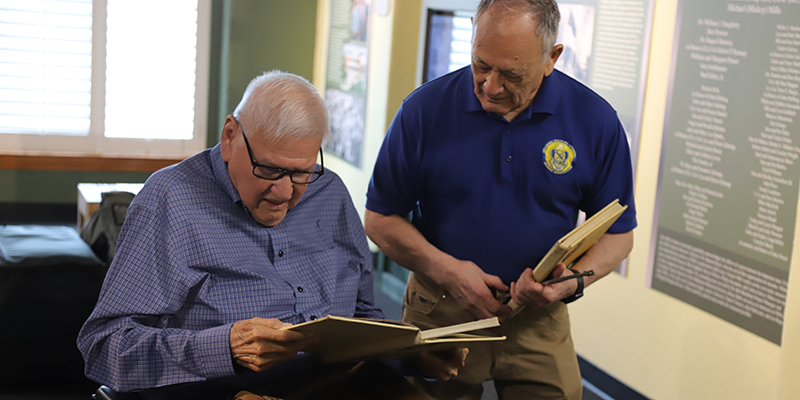

Traveling with his wife and daughter, Lookout, nicknamed “Mogri,” toured the museum, taking in the renovations, upgrades and the memories for his first return to the Hill in nearly 60 years.

“I remember when my dad brought me here – they assigned me to Markham barracks,” Lookout said. “It didn’t take me long to get homesick. Before dad left, he told me – his voice kind of cracking – that he was just as far away as the phone.

“After he left, I sat in my barracks and then a non-com (non-commissioned officer) came in and started telling me what I was going to be doing, giving me a lot of instructions, and I thought ‘What have I gotten myself into?’, but after that, another non-com came in – his name was Barry Baker – and he said ‘Don’t worry, I’ll help you out,’” he said. “Barry was a nice guy. He had red hair. We started talking and later, a sergeant came in and I found out when an officer enters the room, you stand up. I learned that rank played a big role here.”

Although Lookout said it took him a while to acclimate to his new environment, having been raised around a predominantly Native American community, he eventually grew familiar with his time at the military academy and came to appreciate the lessons being taught him and the confidence being instilled.

“The experience I got here was very valuable. I may not have known it at the time, but as I got out into the world, into the public more, I realized I’d been taught how to conduct myself, how to be a better person,” he said. “Loyalty, integrity, honesty – all virtues you need to have, I was taught at the academy, and they served me after I got out.”

Lookout, one of the last remaining full bloods of the Osage Nation, took those lessons learned and – long before he returned to honor his past at OMA – he honored his past, and his culture, in another way in being instrumental in preserving the Osage language.

“I grew up hearing Osage (spoken) my whole life, but it wasn’t until I was in my 30s that I became interested in learning the language,” he said. “I thought it would always be around, but by that point – around 1971 or 1972 – it had started dying out, and I felt it was important to save (the language) so future generations could hear and learn it. It’s an important part of our people, one that I didn’t want to be lost.”

Even after Lookout was told by an older relative to “let the language go,” the desire to learn the language so integral to his culture never left him, particularly with so many of his fellow Osage wanting to know how to pray in their own language.

“That’s one thing dad had told me, was that he could teach me how to pray (in Osage), because he could pray the old way,” he said. “So, he taught me to pray, but it was harder for me to learn conversational Osage, in part, because there was no orthography (conventional spelling system of a language). They would say ‘Just write it down the way you hear it,’ which I did, but when I got home, I couldn’t read it.

“Soon, I realized we would have to use symbols to circumvent the problem of writing down Osage (words) using the English alphabet,” he continued.

Lookout then spent the next 40 years learning and teaching the Osage language, including developing an Osage orthography, which laid the groundwork for the Osage people and other Native nations to strengthen their culture and sovereignty, preserving their identity through their language.

Today, Lookout – the grandson of Osage Chief Fred Lookout, who went on the last buffalo hunt with the tribe when he was 12 – is credited with being fundamental in the preservation of the Osage language.

He was the Kansas State University Language Department’s first director; led the team which developed the Osage orthography; worked with Google to transform the orthography into Unicode, making it possible for Osages everywhere to write the orthography on any digital platform; and in 2021, he received an Honorary Doctorate in Education from KSU for his efforts.

Lookout’s voice is recognized by Osages everywhere, as he has prayed in Osage at countless dinners, events, meetings, cultural events, prayer meetings, funerals and more.

Now in his 80s, Lookout is hoping his work can continue, allowing future generations to continue praying and speaking in Osage, and that the language will live forever.

“Our language is our identity. We can’t lose that,” he said.

Even as Lookout has left a legacy with the preservation of his past through the Osage language, he said he’s “humbled” to return to Claremore to visit the OMA Museum which has preserved another aspect of Lookout’s past.

“It’s humbling to be back here. I don’t think I’ve been here in almost 60 years,” he said. “It’s so different, but it’s so good to see the museum preserving the past, honoring all the young men who came through here, all they did, all they gave. It’s tremendous to see (the OMA Museum). I’m very proud to see it this way.”

For more information about the Oklahoma Military Academy Museum, visit www.rsu.edu/OMAmuseum.